You’ve probably stood in front of a cooler, glanced at the neon bottles, and wondered—is Gatorade an energy drink or something else entirely? On busy training days, the difference matters. Classic Gatorade is formulated as a sports drink: it helps replace fluids and electrolytes while supplying quick carbohydrates during longer or sweatier efforts. Energy drinks, by contrast, exist to stimulate with caffeine (often alongside other actives). That may sound like a small distinction, yet in practice it changes when each beverage makes sense, how your body responds, and what outcomes you can expect over a season.

To set the stage, consider purpose. A sports drink supports hydration under load; an energy drink boosts alertness through central nervous system stimulation. Although both can coexist in an athlete’s toolkit, they solve different problems. Consequently, your choice should follow your training context, not the color of the bottle or the marketing vibe.

Also Read: Electrolyte Drinks for Hangovers: 5 Easy DIY Recipes to Rehydrate Fast

Is Gatorade an Energy Drink—or a Sports Drink?

At its core, the flagship Gatorade Thirst Quencher line is built for performance hydration. The brand’s pages describe formulations centered on sodium, potassium, and carbohydrate to help maintain fluid balance and supply fuel when sweat losses climb (see the concise Gatorade product overview). Meanwhile, energy drinks are typically framed around measurable caffeine doses—commonly 80–200 mg per serving—to raise alertness quickly. In other words, one is designed to keep you going when conditions are tough; the other is designed to perk you up when you’re dragging.

Nevertheless, brands evolve. Under the same umbrella, Gatorade Fast Twitch exists as a clearly caffeinated option, positioned for pre-workout or competitive sharpness (here’s the Fast Twitch product page). So while the family includes something that acts like an energy drink, the classic bottle that most of us associate with sidelines and tournaments remains a sports drink first and foremost.

From a lifestyle perspective, it helps to remember public-health basics as well. For day-to-day hydration outside training, water is usually enough, a point repeatedly emphasized in the CDC’s water & healthier drinks guidance. However, as workouts lengthen, heat and humidity rise, or sweat becomes copious, a carbohydrate-electrolyte solution can play a useful role.

Also Read: Is Coffee or Caffeine Bad for GERD?

Does Gatorade Have Caffeine?

Here’s where confusion starts. Classic Gatorade (Thirst Quencher) contains 0 mg caffeine across flavors and formats; you can verify this on PepsiCo Product Facts for representative SKUs (for instance, Cool Blue shows “Caffeine: 0 mg”). So the common bottle you see in coolers is not a stimulant beverage.

By contrast, Gatorade Fast Twitch delivers 200 mg caffeine per 12 oz, a dose that clearly places it in energy-drink territory regarding stimulation. It’s also zero sugar and includes B-vitamins; even so, caffeine tolerance varies widely, so timing and dose deserve attention. Early-morning sessions, back-to-back matches, or long drives to tournaments might be scenarios where that edge helps; late-evening training or recovery days probably aren’t.

Also Read: Pedialyte and Electrolytes for Diarrhea

Does Gatorade “Give You Energy”?

Carb-Based Fuel vs Stimulant Energy

Language trips us up here. In everyday conversation, “energy” can mean pep, buzz, or motivation. Physiologically, however, energy for your working muscles comes from carbohydrate, fat, and (to a lesser extent) protein. Classic Gatorade provides carbohydrates, so it can absolutely fuel efforts that extend in duration or intensity. That said, it isn’t meant to produce a nervous-system jolt—that’s caffeine’s job. Accordingly, separate these ideas: fuel supports muscular work; stimulation sharpens alertness.

When Carbohydrate-Electrolyte Drinks Make Sense

As a practical rule, if your session is short and light—say, a brisk 30-minute jog—water is ideal. If workouts stretch beyond ~60 minutes, conditions are hot/humid, or you notice heavy sweating, a carbohydrate-electrolyte solution can help you maintain pace and reduce late-session drop-off. For those who like to read the underlying framework, the ACSM’s fluid replacement position stand (summary PDF) lays out athlete-oriented rationale without drowning you in jargon.

When a Caffeinated Option Fits (and When It Doesn’t)

Occasionally, alertness is your bottleneck. Perhaps a dawn strength block, a tournament double-header, or a long drive after an event leaves you a bit foggy. In those cases, caffeine can be strategic. Still, 200 mg—the Fast Twitch dose—is substantial for many people. It can improve vigilance, yet it may also undermine sleep or aggravate jitters if mistimed. If you do experiment, consider lower total daily caffeine, keep doses earlier in the day, and pay attention to how your heart rate, sleep quality, and mood respond.

Also Read: Boosting Hydration: The Key Benefits of Drinking More Water

Gatorade vs Energy Drinks: What Actually Differs?

Ingredients & Intent

Sports drinks lean into electrolytes (especially sodium) and carbohydrate to support hydration and performance during extended, sweaty sessions. Energy drinks, on the other hand, center on caffeine (sometimes alongside taurine, guarana, or other actives) to elevate alertness. Consequently, the smartest way to choose is to look at the label: caffeine content, sugar amount, and serving size tell you what job a drink is built to do. For everyday choices outside sport, the CDC’s “Rethink Your Drink” explainer is a simple anchor—water first most of the time, with beverages that fit your context layered on top.

Use-Cases & Timing

In practice, choose a sports drink during 90-minute trainings, tournament days, long runs, or sweltering practices—especially when you can feel salt on your skin or see sweat lines on clothing. Choose an energy drink only if alertness is the limiting factor, and only when you can control caffeine timing so it doesn’t collide with sleep or recovery. During sessions, small, regular sips generally beat infrequent gulps; after, continue with water and a balanced meal so you restore total fluid, electrolytes, and glycogen.

Sugar, Sweeteners, and Preference

Another real-world variable is sweetness. Some athletes prefer the classic sugar-containing profile in the thick of training because it’s both fuel and flavor—a nudge to keep drinking. Others want lower-calorie options for lighter sessions. If you’re in the latter group, you can look at Gatorade Zero on the official site for a no-sugar electrolyte approach (Gatorade Official Site). Meanwhile, if you’d rather keep control in your own kitchen, you can tailor ingredients with our DIY electrolyte roundup—useful when you want a gentler flavor or need to adjust sodium to your sweat rate.

Also Read: Refresh and Recharge: DIY Non-Caffeinated Energy Drinks for Productive Afternoons

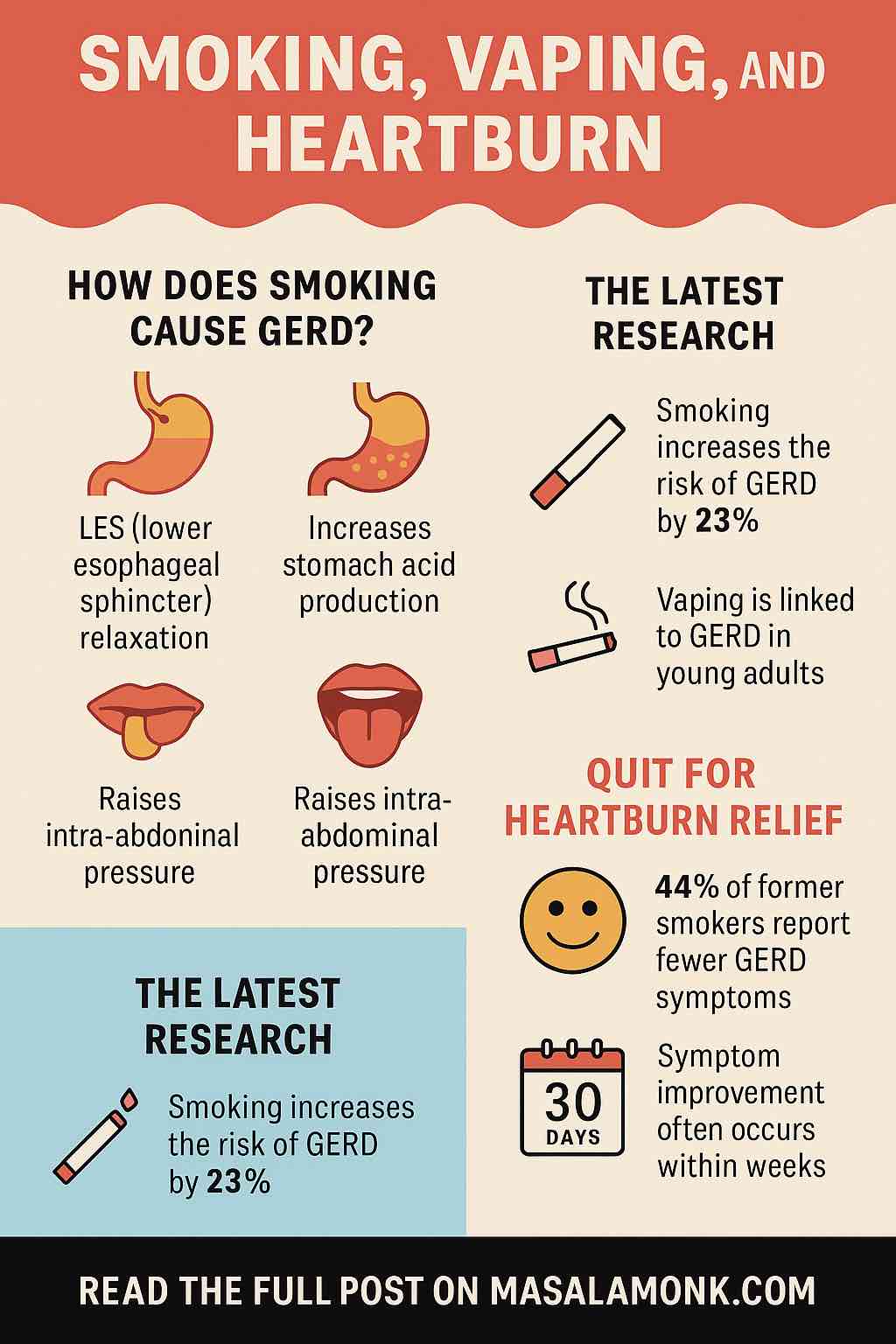

Is Gatorade Good for Acid Reflux or Heartburn?

Acidity Considerations

Many sports drinks are acidic and frequently contain citric acid. For some people living with GERD, acidic drinks can aggravate symptoms; caffeinated beverages can be problematic as well. None of this means you must avoid sports drinks entirely, yet it does suggest a more mindful approach. Sip slowly rather than chugging, avoid drinking on an empty stomach if that reliably triggers discomfort, and observe patterns in your own response. For accessible medical context, the American College of Gastroenterology’s GERD page is a helpful primer.

Gentler Hydration Ideas (Practical, Tasty, Flexible)

If you’re reflux-prone, you might favor lower-acid options on easier days. Coconut water offers a naturally potassium-rich profile and a softer mouthfeel; our ultimate guide to coconut water covers benefits, nutrition, and picking a quality brand. Prefer a more precise approach? Build your own drink at home and control the acidity from the start. Try the DIY electrolyte roundup for straightforward base formulas, then pivot to cooling cucumber electrolyte quenchers when you want ultra-light, hot-weather refreshment. Additionally, if you’re experimenting with lower-sugar blocks for specific training phases, these fasting-friendly electrolyte templates make it easy to match sodium and fluid without overshooting carbs on rest days.

When to Choose Gatorade vs Water

On ordinary days—commutes, desk work, errands—water is the effortless baseline. It’s inexpensive, accessible, and aligned with the CDC’s hydration basics. Yet once your training crosses certain thresholds, a sports drink earns its place. Consider the combination of duration, intensity, environment, and sweat rate. If you’re tackling a two-hour football practice in peak summer, a long tempo run in sticky humidity, or a day-long tournament with limited recovery windows, the trio of fluid + electrolytes + carbohydrate becomes practical rather than optional.

Furthermore, think seasonally. Early in a training cycle, you may be recalibrating to heat, and sweat sodium concentration can vary among individuals. Some athletes notice salt crystals on the skin or brine-like sweat taste; others don’t. Tuning the sodium you drink to how you actually sweat is more impactful than defaulting to “one size fits all.” If you prefer to fine-tune with food you already love, try layering post-workout electrolyte recipes from your pantry staples—our post-workout electrolyte recipes collection offers flexible blueprints that you can scale up for tournament weeks.

Moreover, hydration isn’t just about what you drink during a session. What you do before and after matters. Arrive at practice well-hydrated, sip early and regularly through the session, and continue with water afterward as you eat a proper meal. Over time, those simple rhythms beat last-minute fixes every single time.

Also Read: Benefits of Lemon and Lime Water: Refreshing Hydration with a Citrus Twist

Is Gatorade an Energy Drink—Yes, No, or “It Depends”?

The Everyday Bottle vs the Caffeinated Outlier

It’s tempting to want a binary answer, but the reality is slightly nuanced. Classic Gatorade is not an energy drink; it’s a sports drink with 0 mg caffeine (again, the PepsiCo Product Facts listing for Cool Blue is a simple verification point). That’s the bottle you’ll see most often on sidelines. Fast Twitch, however, is a caffeinated product under the same brand family; at 200 mg per 12 oz, it behaves like a typical high-caffeine energy drink (see Fast Twitch here). Both can be useful, provided you pick the right one for the job.

Choosing Based on the Job You Need Done

Ask yourself: What problem am I solving today? If you need hydration + electrolytes + carbs to maintain effort in heat, the classic sports drink makes sense. If you need alertness, and you can time caffeine without compromising sleep or recovery, a caffeinated option may be appropriate. Conversely, if it’s a short, light session, water is still the simplest, cleanest answer. When you match beverage to job, you’ll feel it in the quality of your training, not just on the scale or in the mirror.

Personalization Without the Hype

Finally, remember you’re not a lab rat; you’re a person with preferences, constraints, and a life outside training. If a particular flavor encourages you to drink enough during a punishing match in June, that’s valuable. If your stomach is happier with a lower-acid mix you blend at home, that’s equally valid. Our readers often start with a base from the DIY electrolyte roundup, then tweak sodium and carb levels to fit their sessions. Others rely on coconut water because it feels gentler on the gut (learn how to choose a good one in the coconut water guide). The point isn’t perfection; it’s fit-for-purpose.

The Bottom Line

If you’re asking is Gatorade an energy drink, the straightforward answer for the everyday bottle is no—it’s a sports drink made to hydrate and fuel through carbohydrates, with 0 mg caffeine. That said, the brand family also includes Fast Twitch, a caffeinated product that functions more like an energy drink at 200 mg per 12 oz. Choose based on the job at hand: water for short and light, sports drink for long and sweaty, and caffeine strategically (and sparingly) when alertness is the true limiter. Along the way, listen to your body, respect your stomach, and keep options you actually enjoy—whether that’s a classic bottle, a no-sugar electrolyte like Gatorade Zero, or a home-mixed solution from our post-workout electrolyte recipes.

Because in training—as in life—consistency beats drama. Hydrate on purpose, and your performance follows.

FAQs

1) Is Gatorade an energy drink?

In short, no. It’s primarily a sports drink designed for hydration and carbohydrate replacement during longer or sweat-heavy activity.

2) Is Gatorade an energy drink—yes or no?

Yes-or-no version: No. Classic Gatorade is a sports drink, not an energy drink, because it doesn’t rely on caffeine for stimulation.

3) Is Gatorade considered an energy drink by athletes?

Strictly speaking, it isn’t. Athletes use it for electrolytes and quick carbs, while energy drinks are chosen for caffeine-driven alertness.

4) Does Gatorade have caffeine?

Generally, classic Gatorade contains 0 mg of caffeine. A separate product line with caffeine exists, but the regular bottle on sidelines is caffeine-free.

5) Does Gatorade give you energy?

Functionally, it provides carbohydrate fuel, which your muscles can use during extended efforts. That’s different from the “buzz” you get from caffeine.

6) Is Gatorade good for energy before a workout?

For short or easy sessions, water typically suffices. For longer, hotter, or more intense workouts, Gatorade’s carbs and electrolytes can help maintain pace.

7) Gatorade vs energy drinks: which is better for training?

It depends on the goal. Choose Gatorade when hydration and electrolytes matter most; choose a caffeinated beverage only when alertness is the limiter.

8) Is Gatorade good for acid reflux or heartburn?

Sometimes it can aggravate symptoms due to acidity; sensitivity varies. If you’re reflux-prone, sip slowly, avoid chugging, and assess personal tolerance.

9) Is Gatorade a good “energy drink” alternative?

Indeed, for sport-specific needs, yes. It supports hydration and fueling without caffeine, which many people prefer during long practices or matches.

10) Is Gatorade an energy drink for everyday use?

Day to day, water is usually the best choice. Reserve Gatorade for workouts, hot conditions, tournaments, or heavy-sweat scenarios.

11) What are Gatorade “energy drink” benefits people talk about?

Chiefly: fluid replacement, electrolytes (notably sodium), and quick carbs to reduce late-session fade during sustained efforts.

12) Is Gatorade Zero an energy drink?

Not at all. It’s a zero-sugar sports drink variant intended for hydration without carbohydrate calories; it still isn’t a caffeine product.

13) Can Gatorade help with cramps?

Potentially, when cramps are related to heavy sweating and electrolyte losses. Nonetheless, total hydration, training status, and pacing also matter.

14) Is Gatorade better than water for a 30-minute workout?

Typically, no. For short, light activity, water is sufficient. Gatorade shines when duration, heat, or sweat rate increase.

15) Is Gatorade an energy drink for students or office days?

Ordinarily, no—there’s no need for sports-drink carbs at a desk. If you’re not sweating or exercising, choose water most of the time.

16) Is Gatorade an energy drink in India?

Designation doesn’t change by country. It remains a sports drink; flavors and availability vary by region.

17) Does Gatorade help with endurance events?

Yes, during marathons, football tournaments, or long rides, the combination of fluid, electrolytes, and carbs can support sustained output.

18) Is Gatorade a good choice if I’m watching sugar?

Sometimes. Consider serving size and timing relative to training. For lighter days, choose lower-sugar hydration or zero-sugar variants.

19) Is Gatorade an energy drink for weight loss?

That’s not its purpose. It’s built for performance hydration. For weight management, prioritize overall diet, activity, and total calorie balance.

20) Can kids use Gatorade during sports?

When practices are long or in hot weather, a sports drink can be appropriate. Otherwise, water remains the default for routine play.

21) Is Gatorade an energy drink review—what’s the verdict?

As a sports drink, it performs as intended: hydration + electrolytes + carbs. As an “energy drink,” the classic version isn’t meant to stimulate.

22) When is Gatorade not necessary?

Short, low-intensity sessions; cool environments; minimal sweating; or non-training contexts—water covers those situations well.

23) Is Gatorade an energy drink compared to pre-workouts?

Pre-workouts focus on stimulants (caffeine) and sometimes other actives. Gatorade focuses on hydration and fueling; they serve different roles.

24) Can Gatorade upset the stomach?

Occasionally, yes—especially if chugged quickly, consumed on an empty stomach, or if you’re sensitive to acidity. Trial strategies and adjust.